The Association Between Adhd and Antisocial Personality Disorder (Aspd) a Review

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Personality disorders and Axis I comorbidity in boyish outpatients with ADHD

BMC Psychiatry volume 16, Article number:175 (2016) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a lifelong condition which carries great cost to society and has an extensive comorbidity. It has been assumed that ADHD is 2 to 5 times more than frequent in boys than in girls. Several studies have suggested developmental trajectories that link ADHD and sure personality disorders. The present study investigated the prevalence of ADHD, mutual Axis I disorders, and their gender differences in a sample of adolescent outpatients. We also wanted to investigate the relationship between ADHD and personality disorders (PDs), every bit well every bit how this relationship was influenced by adjustment for Axis I disorders, historic period and gender.

Methods

We used a sample consisting of 153 adolescents, aged fourteen to 17 years, who were referred to a not-specialized mental wellness outpatient dispensary with a defined catchment area. ADHD, conduct disorder (CD) and other Centrality I conditions were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). PDs were assessed using the Structured Interview for DSM-Iv Personality (SIDP-IV).

Results

13.7 % of the adolescents met diagnostic criteria for ADHD, with no significant gender difference. 21.6 % had at least one PD, 17.6 % had CD, and four.half-dozen % had both ADHD and a PD. There was a significantly elevated number of PD symptoms in adolescents with an ADHD diagnosis (p = 0.001), and this relationship was not significantly weakened when adapted for age, gender and other Axis I disorders (p = 0.026). Antisocial (χ 2 = 21.eighteen, p = 0.002) and borderline (χ ii = 6.15, p = 0.042) PDs were significantly more frequent in girls than in boys with ADHD.

Conclusions

Nosotros establish no pregnant gender difference in the prevalence of ADHD in a sample of adolescents referred to a general mental health outpatient clinic. Adolescent girls with ADHD had more PDs than boys, with hating and deadline PDs significantly different. The nowadays study suggests that ADHD in girls in a general outpatient population may be more prevalent than previously assumed. It particularly highlights the importance of assessing antisocial and deadline personality pathology in adolescent girls presenting with ADHD symptoms.

Background

ADHD and personality disorders

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a mutual and often lifelong status which carries great toll to order and has an extensive psychiatric comorbidity [1–4]. It manifests during early on babyhood, previous to other Centrality I diagnoses, and is associated with a broad range of other health-related bug, such as impulsive behaviors, greater number of traumas, lower quality of life, reduced social functioning, and homelessness, fifty-fifty after adjusting for additional comorbidity [5, 6].

The worldwide prevalence of ADHD has been estimated at about iii–5 % [7, eight], only one study reported a prevalence of 8.5 % [9]. ADHD may be more prevalent than previously assumed [10]. A recent study suggested that the prevalence of ADHD may be increasing, only this could besides be due to increased clinical alertness and improved diagnostic procedures [11].

ADHD is generally considered to be more than prevalent in boys than in girls, with male/female ratio estimates ranging from two:one to 9:1 [eight, 12]. However, ADHD may be experienced by larger numbers of females than has previously been considered [x].

ADHD has been associated with anxiety, mood, and disruptive behavioral disorders [9]. In a sample of twins and siblings no significant gender differences in comorbidity for externalizing disorders were found [13]. In a v-yr follow-up study of a accomplice of children with ADHD, 68.9 % continued to meet total criteria for ADHD, exhibiting high levels of antisocial behavior, criminal activeness and substance use bug [xiv].

In DSM-Iv and DSM-5, personality disorder (PD) categories may be practical to adolescents when the individual's item maladaptive personality traits are pervasive, persistent, and unlikely to exist limited to a particular developmental state or an episode of an Axis I disorder. With the exception of hating PD (ASPD), whatever PD can be diagnosed in a person under xviii years of age if the diagnostic features have been present for at to the lowest degree 1 yr [15, xvi]. Still, in studies on PDs in adolescence, the DSM-Iv age benchmark for ASPD is waived [17–19].

PDs are common, with adult prevalence numbers of 10–fifteen % in the general population [20], up to forty % in outpatient samples, and up to 71 % in inpatient samples [21]. In adolescents, prevalences range from 6 to 17 % in community samples, and in clinical samples from 41 to 64 % [18, xix].

Inquiry supports the assumption that PD symptoms sally at an early age and are related to health-adventure behaviors in adolescence besides as young machismo [22–24], but PDs may have a better prognosis than previously assumed. Maladaptive personality traits may change in severity or expression over fourth dimension; nonetheless they often atomic number 82 to persistent functional impairment and reduced quality of life even if the diagnostic threshold for a specific PD is no longer reached [25, 26].

Borderline PD (BPD) has a lifetime prevalence of 2.7 % in the full general population; it seems to be equally prevalent among men and women [27]. Diagnosing BPD in young persons can be challenging [28], merely at that place is an increasing awareness of predisposing factors and adolescent presentation of BPD [29–33]. Recent work has demonstrated that BPD is as reliable and valid in adolescents every bit in adults [32, 34, 35]. 1 written report suggested that late-latency children are about half every bit likely as adults to meet DSM-IV criteria for BPD [36].

Few studies have reported on gender differences [18] and gender might non play a defining role in symptom expression [36].

ADHD, PDs, and Axis I comorbidity

The question has been posed if ADHD tin can be considered an early stage in the evolution of BPD. A comprehensive literature review establish data that provide a basis for the hypotheses that ADHD is either an early on developmental stage of BPD, or that the ii disorders share an environmental and genetic aetiology [37].

Adults with severe BPD often show a history of childhood ADHD symptoms. Persisting ADHD correlates with the frequency of co-occurring Axis I and PDs [38–41]; for example, the presence of ADHD tends to make BPD more disruptive [42]. A study of treatment refractory adolescents and young adults found unrecognized ADHD in six % of the patients [43].

In prisoners babyhood and adult ADHD symptoms were found to be positively correlated with BPD and negatively correlated with compulsive personality pathology. Axis I disorders were not significantly related to childhood ADHD [44]. A study on probationers with BPD reported essentially more symptoms of ADHD, anxiety and depression compared to subjects without BPD [45].

Several studies have suggested developmental trajectories that link ADHD, bipolar disorder and certain PDs, especially BPD. The exact nature of these aetiological links is not known [41, 46], but mood lability has been suggested as a mutual denominator [47].

Speranza and colleagues found comorbid ADHD to influence the clinical presentation of adolescents with BPD, and that comorbid ADHD was associated with higher rates of disruptive disorders, with a trend towards a greater likelihood of cluster B PDs and with higher levels of impulsivity, especially of the attentional/cognitive type [42]. Prada and colleagues institute that ADHD and BPD-ADHD patients show a college level of impulsivity than BPD and command subjects [48].

Individuals diagnosed with childhood ADHD were found to be at increased gamble for PDs in late adolescence, specifically borderline (OR = 13.16), antisocial (OR = 3.03), avoidant (OR = 9.77), and narcissistic (OR = viii.69) PDs. Those with persistent ADHD were at higher run a risk for antisocial (OR = 5.26) and paranoid (OR = 8.47) PDs only not the other PDs, when compared to those in whom ADHD remitted. These results suggest that ADHD portends risk for adult PDs, but that the risk is neither compatible beyond disorders, nor uniformly related to child or adult diagnostic status [49].

Females with ADHD and BPD seem to share more than clinical features than males [50, 51]; in adult outpatients a significant association between retrospectively assessed ADHD symptoms and current BPD features was found only in the female subsample [52].

Aims

The objective of the present study, performed on a clinical sample of consecutively referred adolescent outpatients, was to

- ane.

Investigate the prevalence of ADHD and common Centrality I disorders, including possible gender differences.

- 2.

Investigate the relationship betwixt ADHD and PDs. Nosotros also wanted to assess the influence of adjusting for Axis I disorders, historic period and gender on the relationship betwixt ADHD and PDs.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of adolescents aged 14–17 years who were referred to a mental wellness outpatient dispensary for children and adolescents in Oslo (The Nic Waal Plant, Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital). The Nic Waal Found is serving iv city districts with a population of mixed socioeconomic status, representing all social classes including immigrant workers and well-educated middle and upper grade families. The catchment area comprises a total population of 25, 000 children and adolescents from 0 to 17 years of historic period.

Study inclusion took place from Feb 2005 to April 2007. Exclusion criteria were the demand for immediate hospitalization or other urgent therapeutic measures, clinically assessed mental retardation, lack of fluency in the Norwegian language, and absence of the evaluator at the time of referral.

Measures

ADHD

A primary screening for ADHD was performed using the half dozen-particular Developed ADHD Cocky-Report Scale Screener version 1.one (ASRS Screener) in a Norwegian translation [53]. The ASRS Screener is derived from the 18-particular ASRS 1.1 Symptom Checklist [54] and is designed to screen for and approximate the prevalence of ADHD in community samples, also every bit in population surveys and at an private level. The measure is reliable and valid in clinical settings [55] and has repeatedly been shown to be in potent concordance with clinician diagnoses [56].

If the primary screening with the ASRS Screener was positive, the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview-PLUS (MINI-PLUS) department Due west (ADHD in children/adolescents) was used as a diagnostic exam instrument [57] for a final diagnosis of ADHD.

Axis I disorders

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview version 5.0.0 (MINI) in a Norwegian translation was used for assessing Axis I disorders [57, 58].

Personality disorders

The Structured Interview for DSM-IV (SIDP-4) [59] in a Norwegian version was used to assess PDs. The SIDP-IV is a comprehensive semi-structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV PD (Axis Ii) diagnoses. The SIDP-Iv has been used in numerous studies in dissimilar countries, including Kingdom of norway [60–62]. The SIDP-IV covers xiv DSM-4 Axis II diagnoses as well as CD equally a divide centrality I disorder. The Axis II diagnoses incorporate the 10 standard DSM-Four PDs (paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, borderline, histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial, obsessive-compulsive, dependent, and avoidant PD), the three conditional DSM-4 PDs (self-defeating, depressive, and negativistic PD), and mixed PD.

All questions address the typical or habitual behaviour of the subjects during the last 5 years. Each diagnostic benchmark is rated on a four point scale: "0" = criterion not present; "1" = subthreshold level of the trait present; "2" = criterion existence present for virtually of the last 5 years; and "3" = criterion strongly nowadays. Scores "2" and "three" betoken the presence of a criterion co-ordinate to DSM-IV [59].

In accord with diagnostic exercise applied in other studies on PDs in adolescence, the DSM-IV historic period criterion for ASPD was waived [17]. Due to the participants' age, we besides waived the 5 year symptom duration criterion. Instead we decided to employ 2 years symptom duration as criterion. This is in accordance with the benchmark used in previous studies assessing adolescent personality pathology [17, 18].

Procedures and assessment

The first author assessed all participants. The parents or other legal guardians were not involved in the assessment process. The evaluator, male M.D., with 21 years of clinical feel, was specialist in psychiatry and child and adolescent psychiatry. He was trained in evaluation with SIDP-IV by the 2d author, who was an experienced rater, who had previously evaluated patients and reported from comparable studies [62, 63]. 20 ratings were discussed and plant to be in accordance with the rating of the experienced evaluator. ADHD and other Axis I conditions were likewise assessed past the same evaluator, who had been trained past the translator of the Norwegian version of the MINI.

Later completion of the initial assessment, the patients were assigned to further clinical evaluation and handling by clinicians other than the evaluator in the outpatient dispensary.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the relevant mental health condition variables and expressed in mean (SD) and frequency (%) as appropriate. Prevalences of ADHD, other Centrality I conditions and PDs with 95 % Blaker confidence intervals [64] were estimated for the total sample and for each gender separately, with testing for gender differences by exact chi square tests. The full number of ADHD criteria and PD criteria was investigated graphically past locally weighted smoothing (lowess) curves. The human relationship of PD with ADHD symptoms, unadjusted and adjusted for gender was investigated by logistic regression.

Adjustment for age and Centrality I disorders was non performed due to the low number of degrees of freedom available. However, the relationship of the number of PD symptoms with ADHD symptoms, unadjusted and adjusted for gender, historic period and important Centrality I disorders (unproblematic phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, psychosis, major depressive episode, dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, CD, and abuse and dependency of alcohol and substances) was investigated past linear regressions wherein multicollinearity was checked by variance aggrandizement cistron (VIF), preferably below 5–10 for all covariates. Differences in unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and regression coefficients were, when necessary, investigated by a bootstrap BCa 95 % conviction intervals based on 10 000 bootstrap replicates [65], with a difference considered as meaning if 0 was outside the interval.

Information were analysed using the IBM SPSS version xx.0 software, with Blaker confidence intervals computed in the R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Republic of austria) bundle BlakerCI and bootstrapping in the R package kicking. Graphical investigations also used R.

Results

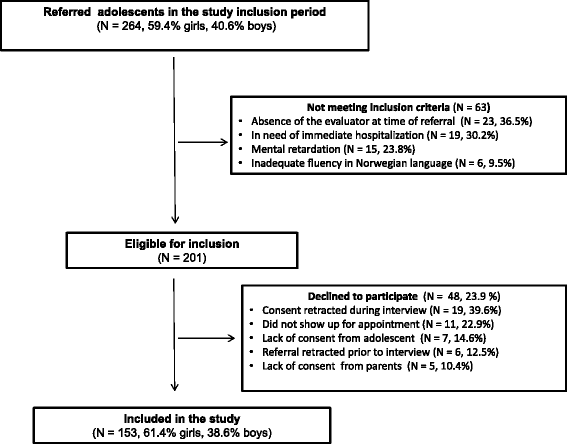

A total of 153 adolescents; hateful age 16.0 years (SD = 1.i, minimum age 14.ane years, maximum age 18.0 years), 61.iv % (Northward = 94) girls were included in the written report. There were no missing data on MINI and SIDP-IV. The flowchart in Fig. 1 illustrates the inclusion process and compunction.

Flowchart of the patient recruitment and selection procedure

Of the participants, 32.7 % (North = fifty) initially screened positive for ADHD using the ASRS Screener. When using the MINI-PLUS as a diagnostic musical instrument, thirteen.7 % (N = 21, 95 % CI 8.9–twenty.1 %) of the adolescents fulfilled all diagnostic criteria for ADHD according to DSM-Iv, with no pregnant gender deviation in prevalence (Table ane).

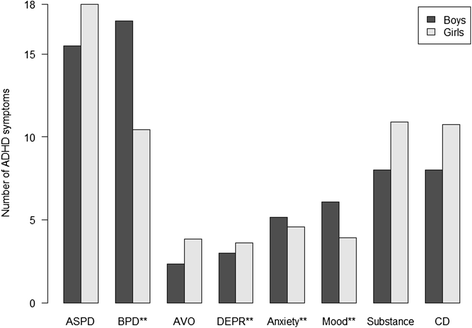

When analysed separately for hyperactivity/impulsiveness and inattention symptoms in each gender, girls had slightly higher overall symptom scores than boys, but the difference was non significant (hyperactivity; χ 2 = 0.xviii, p = 0.786, inattention χ 2 = 0.45, p = 0.668). The male/female ratio was one.19 (95 % CI = ane.12–1.30). The distribution of hyperactivity/impulsiveness and inattention symptoms in dissimilar Centrality I conditions can be seen in Fig. 2.

Frequency of hyperactivity/impulsiveness and inattention symptoms of ADHD by Axis I diagnosis*. * Anxiety: Feet disorders = Simple phobias, Generalized anxiety disorder, Panic disorder, Agoraphobia, Social phobia and Post-traumatic stress disorder; Psychosis: Psychotic disorders; Mood: Mood disorders = Dysthymia and Major depressive episode; OCD: Obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder; CD: Conduct disorder ** p < 0.05

More than two thirds (68.6 %, North = 105) of the adolescents met the criteria for at least i Axis I disorder (76.6 %, N = 72 girls; 56.0 %, N = 33 boys). There were sixteen boys (27.1 %) and forty girls (42.6 %) with more than than one Axis I disorder apart from ADHD (p = 0.060). Feet disorders; uncomplicated phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder (33.3 %, N = 51, 95 % CI 26.0–41.1 %) and mood disorders; dysthymia and major depressive episode (32.7 %, N = 50, 95 % CI 25.iii–40.5 %) were most frequent, followed by substance-related disorders; alcohol and drug corruption or dependence (18.three %, Northward = 28, 95 % CI 12.half-dozen–25.iii %), CD (17.6 %, Northward = 27, 95 % CI 12.2–24.4 %), obsessive-compulsive disorder (9,2 %, N = 14, 95 % CI 5.iii–fourteen.8 %) and psychotic disorders (1.iii %, Northward = ii, 95 % CI 0.2–4.6 %). There were significant gender differences in anxiety (p = 0.022) and mood (p = 0.033) disorders. There were no bipolar, anorectic or bulimic patients in the sample (Table 2).

Of the adolescents, 21.half dozen % (N = 33) had at least i PD, seven.two % (N = 11) had more than one PD, and 4.6 % (N = 7) had both ADHD and a PD. The prevalence of PDs was mostly higher in the referred girls. Every bit shown in Table 3, no significant relationships between ADHD and specific PDs could be ascertained for boys. For girls, nevertheless, in that location were significant relationships betwixt ADHD and ASPD (p = 0.002) and BPD (p = 0.042), as well every bit between ADHD and CD (p = 0.003). Only iii.4 % (Northward = two) of boys and 3.ii % (N = 3) of girls, all with ADHD, matched the criteria for ASPD. There was no significant human relationship with any other PDs (Tabular array 3).

An illustration of the human relationship betwixt ADHD symptoms and relevant Centrality I conditions and PDs is shown in Fig. 3. There were meaning gender differences for BPD (p = 0.032), depressive PD (p = 0.020), anxiety disorders (p = 0.022), and mood disorders (p = 0.033). ASPD (p = 0.409), avoidant PD (p = 0.487), substance use disorders (p = 0.831), and CD (p = 0.585) did not yield significant gender differences.

ADHD symptoms in adolescents with Axis I and personality disorders*. * ASPD = Antisocial personality disorder. BPD = Borderline personality disorder. AVO = Avoidant personality disorder. DEPR = Depressive personality disorder. Feet = Anxiety disorders; Simple phobias, Generalized anxiety disorder, Panic disorder, Agoraphobia, Social phobia and Post-traumatic stress disorder. Mood = Mood disorders; Dysthymia and Major depressive episode. Substance = Substance-related disorders; Alcohol and drug abuse and/or dependence. CD = Conduct disorder **p < 0.05

In that location was no significant relationship between ADHD diagnosis and at to the lowest degree one PD, neither in unadjusted analysis (OR = 2.0, 95 % CI 0.7–v.6, p = 0.164) nor when adjusted for gender (OR = 2.2, 95 % CI 0.8–6.1, p = 0.138). No bootstrap process was considered necessary since these confidence intervals overlapped almost completely. Also, in unadjusted analysis the number of PD criteria was significantly higher (15.7, 95 % CI 6.3–25.1, p = 0.001) when ADHD diagnosis was present. In analysis adjusted for gender, age and Centrality I disorders the respective estimate was 9.6, 95 % CI i.2–18.0, p = 0.026. There was no significant difference between the unadjusted and adapted estimate (95 % CI −0.52–thirteen.43).

Discussion

In the present written report the prevalence of ADHD, mutual Axis I disorders, and gender differences were investigated in an unselected sample of adolescents. The participants were all referred to a non-specialized mental health outpatient clinic with a defined catchment area. Nosotros as well investigated the relationship betwixt ADHD and PD symptoms, besides equally how this relationship was influenced by adjustment for Axis I disorders, age and gender.

We found that 13.seven % of the adolescents met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD. This was in accordance with previous findings, where studies of non-referred adolescents have constitute prevalence rates of 8.v % [9], and prevalence rates in clinical samples are ranging from 11 to 16 % [39, 42]. When applying less strict diagnostic criteria than a definite DSM-Four diagnosis, prevalence rates in clinical samples of more than xxx % have been reported [43]. A like discrepancy between screening and adherence to strict diagnostic criteria was constitute in the present written report, in which 32.7 % of the adolescents screened positively for ADHD when using the ASRS Screener.

Earlier studies of ADHD have reported considerable prevalence differences betwixt boys and girls [7, viii, 12]. In our fabric, however, there was no pregnant ADHD prevalence departure betwixt the male and female person adolescents. In that location was also no significant prevalence difference betwixt genders when nosotros analyzed hyperactivity/impulsiveness and inattention symptoms separately. This probably reflects that our sample was not preselected due to symptom severity or blazon, only the discrepancy is still considerable compared to the commonly assumed male/female ratio of five:1 [12].

More than than two thirds of the adolescents met the criteria for at least i Centrality I disorder, with feet and mood disorders beingness most frequent. There were significant Axis I gender differences only in anxiety (p = 0.022) and mood (p = 0.033) disorders, with girls having the highest prevalence.

Previous studies have reported that the presence of a comorbid ADHD diagnosis influences the clinical presentation of BPD in adolescents [42]. The total prevalence of PDs in our cloth was 21.vi %, which was college than previously reported from adolescent community samples and primary care settings [66], only lower than reported from selected, difficult-to-treat adolescent clinical and juvenile justice samples [xviii, 19, 67–70]. We found higher PD prevalences for girls, with ASPD and BPD reaching significant levels. All girls with ASPD also matched the diagnostic criteria for ADHD. This seems to be in accordance with studies of adults, where females with ADHD and BPD shared more clinical features than males [l, 51], and adult outpatients had a significant association betwixt ADHD and BPD symptoms only in the female subsample [52].

Girls with ADHD were more severely ill than boys, with more Axis I and PD diagnoses. This may in role be explained past a choice bias due to only the near severely affected girls beingness referred to a mental health outpatient clinic. Besides, in general clinical practise in that location may be more focus on assessing and diagnosing adolescent boys than girls presenting with ADHD symptoms, which suggests the possibility of an underestimation of the prevalence of ADHD in adolescent girls. One might speculate that boys are diagnosed with ADHD at a younger age, and that adolescent girls' ADHD symptoms may be inconspicuous by their PD symptoms.

The express data size did not permit us to investigate the relationship between ADHD and unmarried PDs. Nosotros did, all the same, find a significantly elevated number of PD symptoms in adolescents with an ADHD diagnosis (p = 0.001). When adjusted for age, gender and other Axis I disorders, this relationship was even so significant (p = 0.026). Hence, the present report suggests that by using reliability-tested diagnostic interviews like the SIDP-IV, it is viable to assess PDs in adolescents with ADHD, besides in the presence of one or more comorbid Axis I disorders.

Strengths and limitations

The study was performed at a single general service mental health outpatient clinic, receiving adolescents from a geographically defined urban expanse of varied socioeconomic and ethnic population. Nevertheless, the results from the present written report may not be generalizable to other populations. The attrition (23.9 %, N = 48) and the relatively pocket-sized sample size constitute limitations. In item, a limited number of degrees of liberty prevented the inclusion and investigation of interactions of potentially important adjustment variables like ADHD subtype. The participants were included in a limited time span, and we do non know if there were prevalence fluctuations over time.

The gender distribution of our sample was close to identical to the gender distribution of all referred adolescents in the study inclusion menstruum, and reflects the fact that more than boyish girls than boys are referred to Norwegian mental wellness outpatient clinics.

Each patient was diagnosed individually with well-documented semi-structured interviews by a single, experienced clinician and rater. The MINI-PLUS, which utilizes the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria in a strict manner, was used for diagnosing ADHD. This was considered advantageous, equally we did not want to overestimate the prevalence. The evaluator was trained in rating with SIDP-Iv and MINI by experienced evaluators and researchers on PD and Centrality I diagnoses. Still, the use of a single evaluator constitutes a possible limitation. This may take strengthened the internal validity, but might have been a threat to the external validity of the diagnoses.

Conclusions

ADHD is an often lifelong condition with an extensive psychiatric comorbidity [2, 3].

It has been causeless that ADHD is 2 to 5 times more frequent in boys than in girls [7, eight]. We did, even so, not observe a significant gender difference with regard to the prevalence of ADHD in a typical sample of adolescents referred to a non-specialized mental health outpatient clinic. At that place was a significantly elevated number of PD symptoms in adolescents with an ADHD diagnosis, and this relationship did not significantly weaken when adjusted for age, gender and other Axis I disorders.

Girls with ADHD were more severely ill than boys with ADHD; we institute higher PD prevalences for girls, with significant differences for ASPD and BPD. All girls with ASPD met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD.

The present report suggests that ADHD in girls in a full general outpatient population may exist more prevalent than previously causeless. It specially highlights the importance of assessing antisocial and borderline personality pathology in adolescent girls presenting with ADHD symptoms.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ASPD:

-

hating personality disorder

- BPD:

-

deadline personality disorder

- CD:

-

conduct disorder

- ODD:

-

oppositional defiant disorder

- PD:

-

personality disorder

References

-

Lange KW, Reichl S, Lange KM, Tucha L, Tucha O. The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Atten Arrears Hyperactivity Disord. 2010;two(four):241–55.

-

Montejano L, Sasane R, Hodgkins P, Russo L, Huse D. Adult ADHD: prevalence of diagnosis in a US population with employer health insurance. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27 Suppl two:5–eleven.

-

Fischer M, Barkley RA, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult follow-upward of hyperactive children: cocky-reported psychiatric disorders, comorbidity, and the role of childhood conduct problems and teen CD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30(5):463–75.

-

Dalteg A, Zandelin A, Tuninger E, Levander South. Psychosis in adulthood is associated with high rates of ADHD and CD problems during childhood. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68:560.

-

Bernardi S, Faraone SV, Cortese S, Kerridge BT, Pallanti S, Wang S, Blanco C. The lifetime bear upon of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Psychol Med. 2011:i–thirteen. doi: 10.1017/S003329171100153X.

-

Salavera C, Antonanzas JL, Bustamante JC, Carron J, Usan P, Teruel P, Bericat C, Monteagudo Fifty, Larrosa Southward, Tricas JM. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with personality disorders in homeless people. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):916.

-

Polanczyk G, Rohde LA. Epidemiology of attending-deficit/hyperactivity disorder beyond the lifespan. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;xx(4):386–92.

-

Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. A J Psychiatry. 2007;164(half dozen):942–8.

-

Smalley SL, McGough JJ, Moilanen IK, Loo SK, Taanila A, Ebeling H, Hurtig T, Kaakinen Grand, Humphrey LA, McCracken JT. Prevalence and psychiatric comorbidity of attending-arrears/hyperactivity disorder in an boyish Finnish population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1575–83.

-

Brasset-Grundy A, Butler N. Pervalence and adult outcomes of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In: Bedford Group for Lifecourse & Statistical Studies. London: Institute of Education, University of London; 2004. p. 24.

-

Giacobini M, Medin E, Ahnemark E, Russo LJ, Carlqvist P. Prevalence, Patient Characteristics, and Pharmacological Treatment of Children, Adolescents, and Adults Diagnosed With ADHD in Sweden. J Atten Disord. 2014. Epub ahead of print.

-

Staller J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in girls: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2006;twenty(2):107–23.

-

Levy F, Hay DA, Bennett KS, McStephen G. Gender differences in ADHD subtype comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(four):368–76.

-

Langley One thousand, Fowler T, Ford T, Thapar AK, van den Bree K, Harold Grand, Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC, Thapar A. Adolescent clinical outcomes for immature people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):235–forty.

-

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

-

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders - DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Clan; 2013.

-

Chanen AM, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Allot KA, Clarkson V, Yuen HP. Two-year stability of personality disorder in older adolescent outpatients. J Personal Disord. 2004;18(6):526–41.

-

Kongerslev M, Chanen A, Simonsen Eastward. Personality disorder in childhood and adolescence comes of age: a review of the current show and prospects for future research. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;three(1):31–48.

-

Kongerslev M, Moran P, Bo S, Simonsen E. Screening for personality disorder in incarcerated boyish boys: preliminary validation of an adolescent version of the standardised assessment of personality - abbreviated scale (SAPAS-AV). BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:94.

-

Cramer V, Torgersen Due south, Kringlen Eastward. Socio-demographic weather condition, subjective somatic wellness, Axis I disorders and personality disorders in the common population: The relationship to quality of life. J Personal Disord. 2007;21(v):552–67.

-

Zimmerman Thousand, Chelminski I, Immature D. The frequency of personality disorders in psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):405–twenty.

-

Caspi A. The child is father of the human: personality continuities from childhood to machismo. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(1):158–72.

-

Caspi A, Begg D, Dickson Northward, Harrington H, Langley J, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Personality differences predict wellness-risk behaviors in immature adulthood: prove from a longitudinal report. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73(5):1052–63.

-

Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne B, Amell JW, Theodore RF, Moffitt TE. Children's behavioral styles at age iii are linked to their adult personality traits at age 26. J Pers. 2003;71(four):495–513.

-

Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Gunderson JG, Pagano ME, Yen S, Zanarini MC, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Morey LC. Two-year stability and change of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):767–75.

-

Skodol AE. Longitudinal course and outcome of personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin Due north Am. 2008;31(3):495–503.

-

Trull TJ, Jahng Southward, Tomko RL, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. J Pers Disord. 2010;24(4):412–26.

-

Singh MK, Ketter T, Chang KD. Distinguishing bipolar disorder from other psychiatric disorders in children. Current psychiatry reports. 2014;16(12):516.

-

Cicchetti D, Crick NR. Precursors and various pathways to personality disorder in children and adolescents. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(3):683–5.

-

De Fruyt F, De Clercq B. Antecedents of personality disorder in babyhood and adolescence: toward an integrative developmental model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;ten:449–76.

-

Helgeland MI. Prediction of severe psychopathology from adolescence to adulthood. Oslo: Academy of Oslo; 2004.

-

Helgeland MI, Torgersen S. Developmental antecedents of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(ii):138–47.

-

Chanen AM, Kaess Thou. Developmental pathways to borderline personality disorder. Current psychiatry reports. 2012;14(1):45–53.

-

Shiner RL. The development of personality disorders: perspectives from normal personality evolution in childhood and adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(3):715–34.

-

Kaess M, Brunner R, Chanen A. Borderline personality disorder in boyhood. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):782–93.

-

Zanarini MC, Horwood J, Wolke D, Waylen A, Fitzmaurice G, Grant BF. Prevalence of DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder in Two Community Samples: 6,330 English 11-Year-Olds and 34,653 American Adults. J Pers Disord. 2011;25(five):607–19.

-

Storebo OJ, Simonsen E. Is ADHD an early phase in the development of borderline personality disorder? Nord J Psychiatry. 2013. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.841992.

-

Rey JM, Morris-Yates A, Singh M, Andrews G, Stewart GW. Continuities between psychiatric disorders in adolescents and personality disorders in young adults. A J Psychiatry. 1995;152(6):895–900.

-

Philipsen A, Limberger MF, Lieb K, Feige B, Kleindienst Northward, Ebner-Priemer U, Barth J, Schmahl C, Bohus M. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder equally a potentially aggravating factor in borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):118–23.

-

Storebo OJ, Simonsen E: The Association Between ADHD and Hating Personality Disorder (ASPD): A Review. J Atten Disord. 2013. Epub ahead of print

-

Fossati A, Novella 50, Donati D, Donini M, Maffei C. History of childhood attending arrears/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and deadline personality disorder: a controlled study. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):369–77.

-

Speranza G, Revah-Levy A, Cortese S, Falissard B, Pham-Scottez A, Corcos 1000. ADHD in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;xi:158.

-

Vidal R, Barrau Five, Casas Thou, Caballero-Correa M, Martinez-Jimenez P, Ramos-Quiroga JA. [Prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in outpatient adolescents and young adults with other psychiatric disorders refractory to previous treatments]. Revista de psiquiatria y salud mental. 2014;seven(3):104–12.

-

Gudjonsson GH, Wells J, Young S. Personality Disorders and Clinical Syndromes in ADHD Prisoners. J Atten Disord. 2010. doi: x.1177/1087054710385068.

-

Wetterborg D, Langstrom Northward, Andersson G, Enebrink P. Borderline personality disorder: Prevalence and psychiatric comorbidity among male offenders on probation in Sweden. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;62:63–70.

-

Kerekes N, Brandstrom S, Lundstrom S, Rastam M, Nilsson T, Anckarsater H. ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, temperament, and character: phenotypical associations and etiology in a Swedish childhood twin study. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(viii):1140–7.

-

Eich D, Gamma A, Malti T, Vogt Wehrli Yard, Liebrenz M, Seifritz Due east, Modestin J. Temperamental differences between bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and attention arrears/hyperactivity disorder: some implications for their diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:101–iv.

-

Prada P, Hasler R, Baud P, Bednarz Thousand, Ardu S, Krejci I, Nicastro R, Aubry JM, Perroud N. Distinguishing borderline personality disorder from adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a clinical and dimensional perspective. Psychiatry Res. 2014;217(ane–2):107–14.

-

Miller CJ, Flory JD, Miller SR, Harty SC, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the emergence of personality disorders in adolescence: a prospective follow-up report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(9):1477–84.

-

Philipsen A, Feige B, Hesslinger B, Scheel C, Ebert D, Matthies S, Limberger MF, Kleindienst N, Bohus G, Lieb K. Deadline typical symptoms in adult patients with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Atten Deficit and Hyperactivity Disord. 2009;i(1):eleven–eight.

-

van Dijk Iron, Lappenschaar M, Kan CC, Verkes RJ, Buitelaar JK. Symptomatic overlap between attending-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and deadline personality disorder in women: the role of temperament and character traits. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):39–47.

-

Fossati A, Gratz KL, Borroni Southward, Maffei C, Somma A, Carlotta D. The human relationship betwixt childhood history of ADHD symptoms and DSM-IV borderline personality disorder features amongst personality matted outpatients: The moderating office of gender and the mediating roles of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity. Compr Psychiatry. 2014. doi: ten.1016/j.comppsych.2014.09.023.

-

Adler LA, Spencer T, Faraone SV, Kessler RC, Howes MJ, Biederman J, Secnik K. Validity of pilot Adult ADHD Self- Report Scale (ASRS) to Rate Adult ADHD symptoms. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;xviii(3):145–8.

-

Adler LA, Shaw DM, Spencer TJ, Newcorn JH, Hammerness P, Sitt DJ, Minerly C, Davidow JV, Faraone SV. Preliminary exam of the reliability and concurrent validity of the attention-arrears/hyperactivity disorder self-report scale v1.i symptom checklist to rate symptoms of attention-arrears/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(3):238–44.

-

Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi Eastward, Howes MJ, Jin R, Secnik M, Spencer T. The Globe Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Study Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–56.

-

Kessler RC, Adler LA, Gruber MJ, Sarawate CA, Spencer T, Van Burden DL. Validity of the World Health Arrangement Adult ADHD Cocky-Written report Scale (ASRS) Screener in a representative sample of health plan members. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16(2):52–65.

-

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan G, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller Eastward, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (One thousand.I.Northward.I): The evolution and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33.

-

Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan Yard, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan Grand, Dunbar M. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) co-ordinate to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry. 1997;12(five):232–41.

-

Pfohl B BNZM. Structured Interview for DSM-Four Personality (SIDP-IV). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Printing; 1997.

-

Roysamb E, Kendler KS, Tambs One thousand, Orstavik RE, Neale MC, Aggen SH, Torgersen S, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The joint structure of DSM-Iv Axis I and Axis Ii disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120(1):198–209.

-

Helgeland MI, Kjelsberg Due east, Torgersen S. Continuities between emotional and disruptive beliefs disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. A J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1941–vii.

-

Torgersen S, Kringlen Eastward, Cramer Five. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):590–6.

-

Torgersen S. Prevalence, sociodemographics, and functional impairment. In: Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS, editors. Essentials of personality disorders. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2009. p. 417.

-

Blaker H. Confidence curves and improved exact confidence intervals for discrete distributions. Tin can J Stat. 2000;28(4):783–98.

-

Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton: CRC Press LLC; 1993.

-

Johnson JG Exist, Bornstein RF, Sneed JR. Boyish personality disorders. In: Behavioral and emotional disorders in children and adolescents: Nature, cess, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. p. 463–84.

-

Feenstra DJ, Busschbach JJV, Verheul R, Hutsebaut J. Prevalence and comorbidity of Axis I and Centrality Ii disorders among treatment refractory adolescents admitted for specialized psychotherapy. J Personal Disord. 2011;25(6):842–fifty.

-

Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Quinlan DM, Walker ML, Greenfeld D, Edell WS. Frequency of personality disorders in ii historic period cohorts of psychiatric inpatients. A J Psychiatry. 1998;155(ane):140–ii.

-

Lader D, Singleton Due north, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among young offenders in England and Wales. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15(1–ii):144–7.

-

Gosden NP, Kramp P, Gabrielsen Chiliad, Sestoft D. Prevalence of mental disorders among 15-17-year-old male boyish remand prisoners in Denmark. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107(2):102–10.

Acknowledgements

We thank the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authorisation, the Heart for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Eastern and Southern Kingdom of norway, and Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital for their generous back up of this report.

Funding

This study has been funded by grants from the South-Eastern Norway Regional Wellness Authority, the Center for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Eastern and Southern Norway, and Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital.

Availability of information and materials

The data set supporting the results of this article is available upon asking from the beginning author, Hans Ole Korsgaard.

Authors' contributions

All authors have contributed to the groundwork, design, and drafting of the manuscript. HOK did all the assessment work. HOK, TWL and RU performed the statistical analysis. All authors take read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Consent for publication

The ethical approval and consent to participate included consent for publication.

Ideals approval and consent to participate

The report was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics for Eastern Kingdom of norway (REK: 11395) and by The Norwegian Information Inspectorate. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients, and for patients younger than sixteen years written consent was additionally obtained from their parents or other legal guardians.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/aught/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Korsgaard, H.O., Torgersen, Due south., Wentzel-Larsen, T. et al. Personality disorders and Axis I comorbidity in adolescent outpatients with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 16, 175 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0871-0

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0871-0

Keywords

- ADHD

- Axis I

- Comorbidity

- Conduct disorder

- Personality disorder

- Boyish

- Outpatient

Source: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-016-0871-0

Post a Comment for "The Association Between Adhd and Antisocial Personality Disorder (Aspd) a Review"